Pallab GhoshScience Correspondent

David Braun

David BraunThe very first humans millions of years ago may have been inventors, according to a discovery in northwest Kenya.

Researchers have found that the primitive humans who lived 2.75 million years ago at an archaeological site called Namorotukunan used stone tools continuously for 300,000 years.

Evidence previously suggested that early human tool use was sporadic: randomly developed and quickly forgotten.

The Namorotukunan find is the first to show that the technology was passed down through thousands of generations.

According to Prof David Braun, of George Washington University, in Washington DC, who led the research, this find, published in the journal Nature Communications, provides incredibly strong evidence for a radical shake-up in our understanding of human evolution.

“We thought that tool use could have been a flash in the pan and then disappeared. When we see 300,000 years of the same thing, that’s just not possible,” he said.

“This is a long continuity of behaviour. That tool use in (humans and human ancestors) is probably much earlier and more continuous than we thought it was.”

David Braun

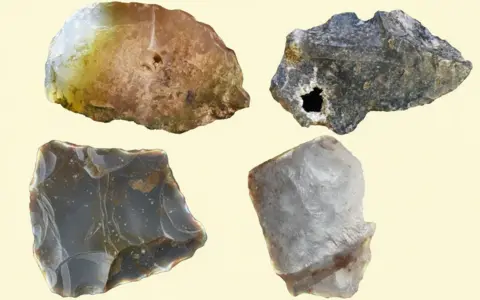

David BraunArchaeologists spent ten years at Namorotukunan uncovering 1,300 sharp flakes, hammerstones, and stone cores, each made by carefully striking rocks gathered from riverbeds. These are made using a technology known as Oldowan and is the first widespread stone tool-making method.

The same kinds of tools appear in three distinct layers. The deeper the layer the further back the snapshot in time. Many of the stones were specially chosen for their quality, suggesting that the makers were skilled and knew exactly what they were looking for, according to the senior geoscientist on the research team, Dr Dan Palcu Rolier of the University of São Paulo in Brazil.

“What we see here in the site is an incredible level of sophistication,” he told BBC News.

“These guys were extremely astute geologists. They knew how to find the best raw materials and these stone tools are exceptional. Basically, we can cut our fingers with some of them.”

Geological evidence suggests that tool use probably helped these people survive dramatic changes in climate.

The landscape shifted from lush wetlands to dry, fire-swept grasslands and semideserts,” said Rahab N. Kinyanjui, senior scientist at the National Museums of Kenya.

These sharp environmental changes would normally force animal populations to adapt through evolution or move away. But the toolmakers in the region managed to thrive by using technology rather than biological adaptation, according to Dr Palcu Rolier.

“Technology enabled these early inhabitants of East Turkana to survive in a rapidly changing landscape – not by adapting themselves, but adapting their ways of finding food.”

The evidence of stone tools at different layers shows that for a long and continuous period, these primitive people flew in the face of biological evolution, finding a way of controlling the world around them, rather than letting the world control them.

And this happened at the very beginning of the emergence of humanity, according to Dr Palcu Rolier.

“Tool use meant that they did not have to evolve by modifying their bodies to adapt to these changes. Instead, they developed the technology they needed to get access to the food: tools for ripping open animal carcasses and digging up plants.”

David Braun

David BraunThere is evidence for this at the site: of animal bones being broken, being cut with these stone tools, which means that through these changes, they were consistently able to use meat as a way of sustenance.

“The technology gives these early inhabitants an advantage, says Dr Palcu Rolier.

“They are able to access different types of foods as environments change, their source of sustenance is changing, but because they have this technology, they can bypass these challenges and access new food.”

David Braun

David BraunAt around 2.75 million years ago, the region was populated by some of the very first humans, who had relatively small brains. These early humans are thought to have lived alongside their evolutionary ancestors: a pre-human group, called australopithecines, who had larger teeth and a mix of chimpanzee and human traits.

The tool users at Namorotukunan were most likely one of these groups or possibly both.

And the finding challenges the notion held by many experts in human evolution that continuous tool use emerged much later, between 2.4 and 2.2 million years ago, when humans had evolved relatively larger brains, according to Prof Braun.

“The argument is that we’re looking at a pretty substantial brain size increase. And so, often the assertion has been that tool use allowed them to feed this large brain.

“But what we’re seeing at Namorotukunan is that these really early tools are used before that brain size increase.”

“We have probably vastly underestimated these early humans and human ancestors. We can actually trace the roots of our ability to adapt to change by using technology much earlier than we thought, all the way to 2.75 million years ago, and probably much earlier.”